Legal immunity for COVID-19 issues is a terrible idea | Editorial

Many workers and employers have acted heroically in the coronavirus crisis, but it cannot be assumed that everyone did. A proposal to give blanket immunity to nursing homes and others goes too far.(John McCall/Sun Sentinel/TNS)

The coronavirus pandemic is the newest opening for the nursing home industry and other lawsuit-prone businesses to lobby for protections against being sued.

They’re working in Washington, Tallahassee and other state capitals for near-total immunity from legal liability for anything having to do with COVID-19.

That’s bad. What’s worse is that they may succeed. The Florida Legislature is primed to immunize every sort of activity from grocery stores to condominium swimming pools.

That would set a terrible precedent for covering up errors of negligence that made a tragic epidemic even worse.

It would likely leave Florida workers who contracted COVID-19 on the job with no relief from worker’s compensation or lawsuits against their employers.

Health workers, first responders and many other workers and employers have acted heroically in this crisis, but it cannot be assumed that everyone did. The truth must be left a way to come out. That’s what courts are for.

There should never be blanket legal immunity for anything, least of all something so tragic as an epidemic that already has killed at least 83,000 Americans.

Of the Floridians who have died of the virus, more than a third were residents or staffers at nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. Such a high toll raises serious questions about compliance with pre-existing standards of care, as well as with government’s late-arriving guidelines.

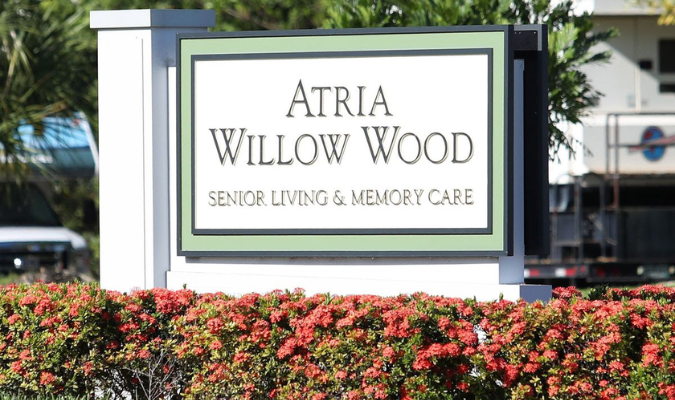

Gov. Ron DeSantis himself took alarm in late March over reports of two deaths at Atria Willow Wood, a Broward assisted living facility that subsequently accounted for seven deaths.

“What the investigation has found out is that construction workers, staff and cooks who were ill were not screened,” he said. “They were allowed to go work their jobs and mix with the residents unimpeded.” He said the matter “could be” criminal.

The management denied his charges, saying several agencies had monitored the facility “each step of the way.” His office did not reply to a question about his follow-up.

Barely two weeks later, the Florida Health Care Association, the main nursing home lobby, wrote DeSantis requesting “immunity from any liability, civil or criminal, for virtually any “act or omission” in the course of providing health care in connection with the epidemic.

The immunity would apply to all health care facilities, including hospitals, if they were following emergency guidelines and acting “in good faith.”

It would not excuse willful misconduct or “gross negligence,” but that exception comes with a loophole as large as the rule. Anything resulting from a “resource or staffing shortage” would not count as evidence of willful misconduct or gross negligence. In plain language, the employer would be off the hook for failing to provide enough masks or other protective equipment.

That’s the devil in the details that would deny any form of financial relief to people who are infected at work.

Staffing shortages are a chronic problem in Florida nursing homes, frequently cited in lawsuits. Yet Florida allows them to be poorly self-insured.

A federal audit of 20 Florida nursing homes, reported by the Tampa Bay Times last week, faulted emergency plans at 16 of them and safety concerns at 19, blaming “inadequate management oversight and staff turnover.” They found “widespread safety failures,” the newspaper said, including inadequate smoke alarms and hazardous materials.

“Why are these residents dying in nursing homes? Because there’s a complete lack of protection,” says Steve Watrel, a Jacksonville lawyer who practices in that field. “If you’re going to talk about immunity, you’ve got to be talking about transparency and more protection.”

Lee Friedland is a Fort Lauderdale attorney who has filed notice of intention to sue Atria Willow Wood over the March 17th death of resident Richard Curran, 72, whose wife remains ill with the virus. Until several years ago, the Currans lived in Cutler Bay.

The lawsuit would claim that a construction crew remained on site after the governor had ordered nursing homes closed to all outsiders. But if nursing homes get the requested protection, Friedland said, “there is no case, it’s gone.”

Rank-and-file workers across the nation, including nurses, hospital orderlies and grocery clerks, potentially have much to lose from blanket immunity. They also have sickened and died from it, sometimes after being ordered not to wear masks lest they scare away customers.

The same push for immunity is happening in other state capitals, as well as in Washington, where Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has tied this push for “tort reform” to any additional aid for state governments he had said should go bankrupt.

In the Florida Legislature, Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, a frequent point man for “tort reform,” wants qualified immunity for every sort of activity, not just in health care. Businesses that forbade their employees to wear masks or take time off when they fell ill would surely welcome that development. So would homeowners’ associations that worry about reopening their swimming pools; Brandes says he’s been hearing from them, too.

The protection, Brandes said, would apply only to actions conforming with official guidelines during the pandemic, but even that limitation raises serious questions. The Centers for Disease Control was rather late in recommending facial masks for everyone, long after many American workers sought them in vain. And President Trump is suppressing the CDC’s latest recommendations.

Would the federal government’s lackadaisical response, or the halting measures Florida eventually took, provide cover for poor decisions in commerce and long-term care?

“As business owners open their doors, they don’t know what risks they’re taking,” Brandes argues. “Actually, I think this provision improves public health, because it gives business an enormous incentive to follow the guidelines.”

But this incentive is too enormous and the guidelines are being relaxed too rapidly.

Blanket immunity goes too far.

Editorials are the opinion of the Sun Sentinel Editorial Board and written by one of its members or a designee. The Editorial Board consists of Editorial Page Editor Rosemary O’Hara, Sergio Bustos, Steve Bousquet and Editor-in-Chief Julie Anderson.